By Cat Sandoval

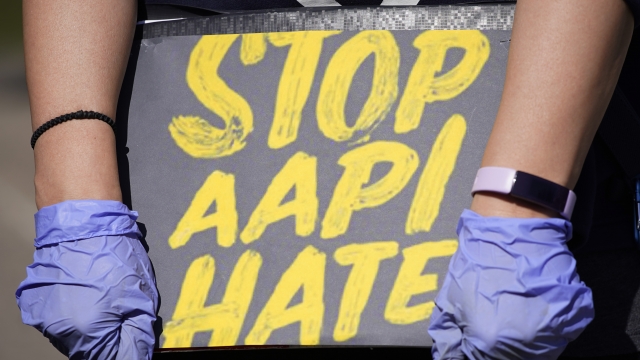

Experts say the trope of Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners and treated as "others" continues today with dangerous consequences.

There aren't many headlines or news coverage of anti-Asian hate crimes now, compared to what was shown during the height of the pandemic — but attacks and insults are still happening in various parts of the country.

The national coalition Stop Asian American Pacific Islander Hate tracked 11,500 hate incidents from March 2020 to March 2022. At the start of the pandemic, Asians were scapegoated and wrongfully blamed for COVID-19. It is true that the Chinese government silenced their doctors and kept the outbreak a secret from the rest of the world.

John C. Yang, is the president and executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice.

"We should be calling out that government. But in doing so, we absolutely need to be clear that it's a government that we are concerned about and not the people," said Yang.

Politicians like former President Donald Trump publicly blamed China and continued to use radicalized terms like "Wuhan virus" and "China virus," terms the World Health Organization warned could lead to racial profiling and stigma. Trump's first "Chinese virus" tweet was followed by an increase in anti-Asian hashtags. But activists say anti-Asian hate didn't start with the pandemic.

Stewart Khow, co-founded the Asian American Education Project.

"There was a political party built, the Workingmen's party that was established in California. That main point was to get rid of the Chinese. So there was violence," said Khow.

Khow is referring to an American Labor Organization founded in San Francisco in 1877. Five years later, anti-Asian sentiments led to the Chinese Exclusion Act. That was the first and only federal law that banned immigration of a specific nationality.

Experts say the trope of Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners and treated as "others" continues today with dangerous consequences.

"Regardless of how long we've been in the United States, whether we were born here or not, that we are seen as a foreigner," said Yang.

During WWII, Japanese Americans, men, women and children were rounded up and placed in detention camps. They were incarcerated for three years, their property and personal items taken.

"Not one Japanese American was ever convicted for spying for Japan," said Khow.

Then, when the Twin Towers fell in 2001, South Asians and Muslim Americans were targeted. It didn't matter if they were born here.

"Hundreds of South Asians and Muslim Americans were singled out, brutalized, and some were killed in a wave of Islamophobia after 9/11," said Khow.

Janelle Wong, is a professor of American studies, at the University of Maryland.

"This is a cyclical kind of trope that is always kind of beneath the surface, but arises in times where the U.S. feels under threat," said Wong.

And now, during the pandemic, experts say one way to combat hate is through education.

"You prevent that from making sure people understand that Asian Americans are American, are part of the fabric of our history," said Yang.

The Asian American Education Project aims to train teachers and teach this history in every public school from kindergarten through 12th grade. Currently, five states have passed a mandatory Asian American history requirement.

"Asian American history, is American history. Let me say it again. Asian American history, is American history. You don't understand big parts of American history — unless you understand Asian American history," said Khow.

The surge in anti-Asian hate has led to a reemergence and groundswell of Asian American activism. In the 80s there was no justice for Vincent Chin, who was killed in a brutal racial attack in Detroit over rising tensions over Japanese auto imports.

Compare that to the reaction after the 2021 mass killing of eight people — mostly Asian women, at massage parlors in metro Atlanta.

"The fact that President Biden went down to Atlanta, along with the vice president, almost immediately after the Atlanta murders, and that there was legislation passed within a within a couple of months addressing hate crimes against Asian Americans — power to Black people, power to Asian people," said Yang.

"One of the most exciting kinds of activism to emerge from the last two years is Asian-American young people's interest in telling their own stories," said Wang.

Chicago held its first ever Blasian March, a coalition of stop anti-Asian hate and Black Lives Matter activists.

Rohan, is the founder of Blasian March.

"I think being Blasian and being a Black Asian is incredibly powerful because, you know, so often society is trying to divide us and separate us. But you can't separate me. You know, I am living proof that we can coexist," said Rohan.

"We can unite as a community from the Black and Asian and Asian communities to come together and just understand our differences and also just celebrate our intersectionality and our history together," said Kate Ventrina, the Chicago Blasian March organizer.