By Matthew Kirschenbaum

What if, in the end, we are done in not by intercontinental ballistic missiles or climate change, not by microscopic pathogens or a mountain-size meteor, but by … text? Simple, plain, unadorned text, but in quantities so immense as to be all but unimaginable—a tsunami of text swept into a self-perpetuating cataract of content that makes it functionally impossible to reliably communicate in any digital setting?

Our relationship to the written word is fundamentally changing. So-called generative artificial intelligence has gone mainstream through programs like ChatGPT, which use large language models, or LLMs, to statistically predict the next letter or word in a sequence, yielding sentences and paragraphs that mimic the content of whatever documents they are trained on. They have brought something like autocomplete to the entirety of the internet. For now, people are still typing the actual prompts for these programs and, likewise, the models are still (mostly) trained on human prose instead of their own machine-made opuses.

But circumstances could change—as evidenced by the release last week of an API for ChatGPT, which will allow the technology to be integrated directly into web applications such as social media and online shopping. It is easy now to imagine a setup wherein machines could prompt other machines to put out text ad infinitum, flooding the internet with synthetic text devoid of human agency or intent: gray goo, but for the written word.

Exactly that scenario already played out on a small scale when, last June, a tweaked version of GPT-J, an open-source model, was patched into the anonymous message board 4chan and posted 15,000 largely toxic messages in 24 hours. Say someone sets up a system for a program like ChatGPT to query itself repeatedly and automatically publish the output on websites or social media; an endlessly iterating stream of content that does little more than get in everyone’s way, but that also (inevitably) gets absorbed back into the training sets for models publishing their own new content on the internet. What if lots of people—whether motivated by advertising money, or political or ideological agendas, or just mischief-making—were to start doing that, with hundreds and then thousands and perhaps millions or billions of such posts every single day flooding the open internet, commingling with search results, spreading across social-media platforms, infiltrating Wikipedia entries, and, above all, providing fodder to be mined for future generations of machine-learning systems? Major publishers are already experimenting: The tech-news site CNET has published dozens of stories written with the assistance of AI in hopes of attracting traffic, more than half of which were at one point found to contain errors. We may quickly find ourselves facing a textpocalypse, where machine-written language becomes the norm and human-written prose the exception.

Like the prized pen strokes of a calligrapher, a human document online could become a rarity to be curated, protected, and preserved. Meanwhile, the algorithmic underpinnings of society will operate on a textual knowledge base that is more and more artificial, its origins in the ceaseless churn of the language models. Think of it as an ongoing planetary spam event, but unlike spam—for which we have more or less effective safeguards—there may prove to be no reliable way of flagging and filtering the next generation of machine-made text. “Don’t believe everything you read” may become “Don’t believe anything you read” when it’s online.

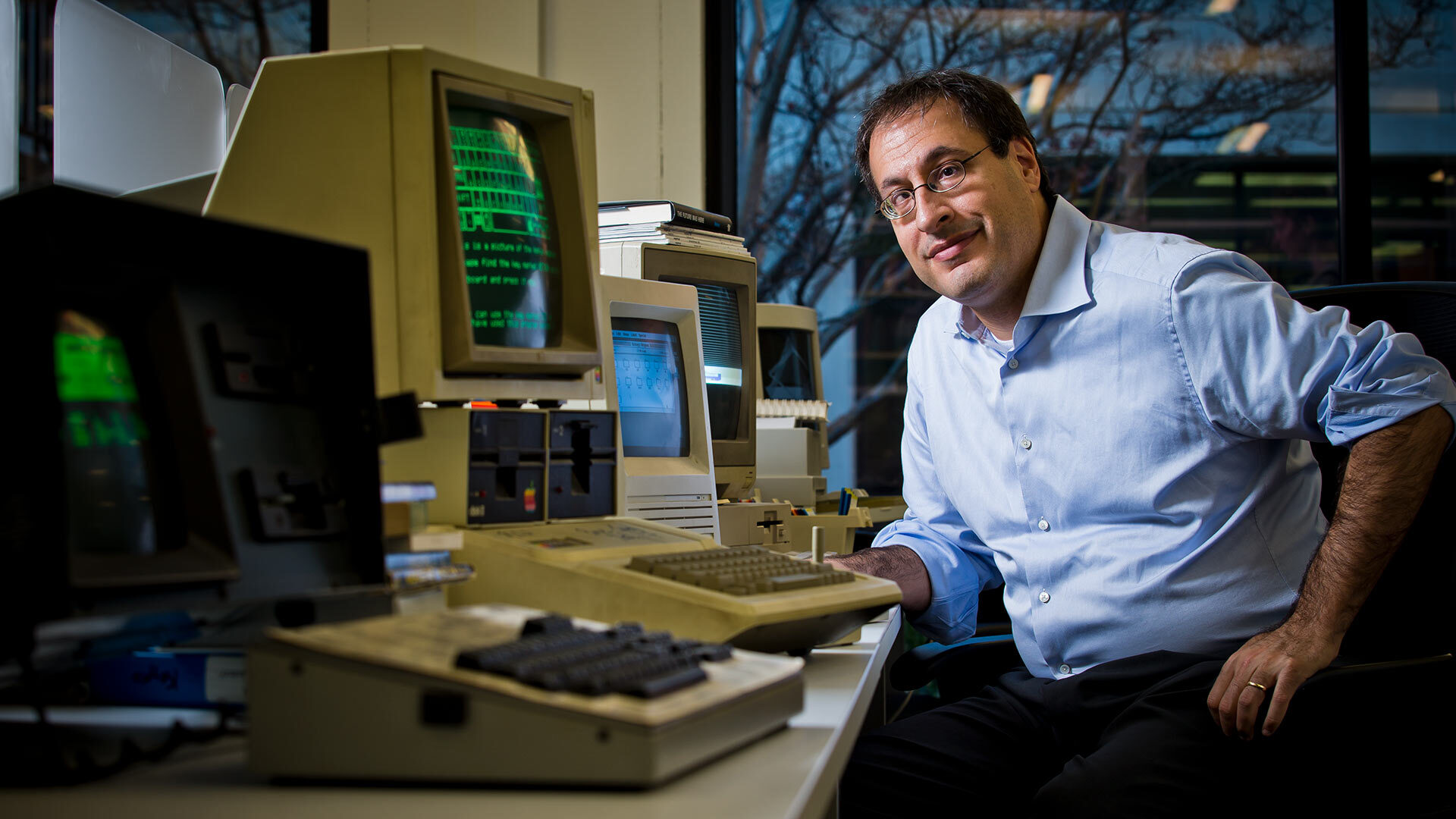

This is an ironic outcome for digital text, which has long been seen as an empowering format. In the 1980s, hackers and hobbyists extolled the virtues of the text file: an ASCII document that flitted easily back and forth across the frail modem connections that knitted together the dial-up bulletin-board scene. More recently, advocates of so-called minimal computing have endorsed plain text as a format with a low carbon footprint that is easily shareable regardless of platform constraints.

But plain text is also the easiest digital format to automate. People have been doing it in one form or another since the 1950s. Today the norms of the contemporary culture industry are well on their way to the automation and algorithmic optimization of written language. Content farms that churn out low-quality prose to attract adware employ these tools, but they still depend on legions of under- or unemployed creatives to string characters into proper words, words into legible sentences, sentences into coherent paragraphs. Once automating and scaling up that labor is possible, what incentive will there be to rein it in?

William Safire, who was among the first to diagnose the rise of “content” as a unique internet category in the late 1990s, was also perhaps the first to point out that content need bear no relation to truth or accuracy in order to fulfill its basic function, which is simply to exist; or, as Kate Eichhorn has argued in a recent book about content, to circulate. That’s because the appetite for “content” is at least as much about creating new targets for advertising revenue as it is actual sustenance for human audiences. This is to say nothing of even darker agendas, such as the kind of information warfare we now see across the global geopolitical sphere. The AI researcher Gary Marcus has demonstrated the seeming ease with which language models are capable of generating a grotesquely warped narrative of January 6, 2021, which could be weaponized as disinformation on a massive scale.

There’s still another dimension here. Text is content, but it’s a special kind of content—meta-content, if you will. Beneath the surface of every webpage, you will find text—angle-bracketed instructions, or code—for how it should look and behave. Browsers and servers connect by exchanging text. Programming is done in plain text. Images and video and audio are all described—tagged—with text called metadata. The web is much more than text, but everything on the web is text at some fundamental level.

For a long time, the basic paradigm has been what we have termed the “read-write web.” We not only consumed content but could also produce it, participating in the creation of the web through edits, comments, and uploads. We are now on the verge of something much more like a “write-write web”: the web writing and rewriting itself, and maybe even rewiring itself in the process. (ChatGPT and its kindred can write code as easily as they can write prose, after all.)

We face, in essence, a crisis of never-ending spam, a debilitating amalgamation of human and machine authorship. From Finn Brunton’s 2013 book, Spam: A Shadow History of the Internet, we learn about existing methods for spreading spurious content on the internet, such as “bifacing” websites which feature pages that are designed for human readers and others that are optimized for the bot crawlers that populate search engines; email messages composed as a pastiche of famous literary works harvested from online corpora such as Project Gutenberg, the better to sneak past filters (“litspam”); whole networks of blogs populated by autonomous content to drive links and traffic (“splogs”); and “algorithmic journalism,” where automated reporting (on topics such as sports scores, the stock-market ticker, and seismic tremors) is put out over the wires. Brunton also details the origins of the botnets that rose to infamy during the 2016 election cycle in the U.S. and Brexit in the U.K.

All of these phenomena, to say nothing of the garden-variety Viagra spam that used to be such a nuisance, are functions of text—more text than we can imagine or contemplate, only the merest slivers of it ever glimpsed by human eyeballs, but that clogs up servers, telecom cables, and data centers nonetheless: “120 billion messages a day surging in a gray tide of text around the world, trickling through the filters, as dull as smog,” as Brunton puts it.

We have often talked about the internet as a great flowering of human expression and creativity. Nothing less than a “world wide web” of buzzing connectivity. But there is a very strong argument that, probably as early as the mid-1990s, when corporate interests began establishing footholds, it was already on its way to becoming something very different. Not just commercialized in the usual sense—the very fabric of the network was transformed into an engine for minting capital. Spam, in all its motley and menacing variety, teaches us that the web has already been writing itself for some time. Now all of the necessary logics—commercial, technological, and otherwise—may finally be in place for an accelerated textpocalypse.

“An emergency need arose for someone to write 300 words of [allegedly] funny stuff for an issue of @outsidemagazine we’re closing. I bashed it out on the Chiclet keys of my laptop during the first half of the Super Bowl *while* drinking a beer,” Alex Heard, Outside’s editorial director, tweeted last month. “Surely this is my finest hour.”

The tweet is self-deprecating humor with a touch of humblebragging, entirely unremarkable and innocuous as Twitter goes. But, popping up in my feed as I was writing this very article, it gave me pause. Writing is often unglamorous. It is labor; it is a job that has to get done, sometimes even during the big game. Heard’s tweet captured the reality of an awful lot of writing right now, especially written content for the web: task-driven, completed to spec, under deadlines and external pressure.

That enormous mid-range of workaday writing—content—is where generative AI is already starting to take hold. The first indicator is the integration into word-processing software. ChatGPT will be tested in Office; it may also soon be in your doctor’s notes or your lawyer’s brief. It is also possibly a silent partner in something you’ve already read online today. Unbelievably, a major research university has acknowledged using ChatGPT to script a campus-wide email message in response to the mass shooting at Michigan State. Meanwhile, the editor of a long-running science-fiction journal released data that show a dramatic uptick in spammed submissions beginning late last year, coinciding with ChatGPT’s rollout. (Days later he was forced to close submissions altogether because of the deluge of automated content.) And Amazon has seen an influx of titles that claim ChatGPT “co-authorship” on its Kindle Direct platform, where the economies of scale mean even a handful of sales will make money.

Whether or not a fully automated textpocalypse comes to pass, the trends are only accelerating. From a piece of genre fiction to your doctor’s report, you may not always be able to presume human authorship behind whatever it is you are reading. Writing, but more specifically digital text—as a category of human expression—will become estranged from us.

The “Properties” window for the document in which I am working lists a total of 941 minutes of editing and some 60 revisions. That’s more than 15 hours. Whole paragraphs have been deleted, inserted, and deleted again—all of that before it even got to a copy editor or a fact-checker.

Am I worried that ChatGPT could have done that work better? No. But I am worried it may not matter. Swept up as training data for the next generation of generative AI, my words here won’t be able to help themselves: They, too, will be fossil fuel for the coming textpocalypse.

-----------

Matthew Kirschenbaum is a professor of English and digital studies at the University of Maryland. He is the author of Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing (Harvard University Press, 2016) and Bitstreams: The Future of Digital Literary Heritage (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021).