By J.J. McCorvey and Char Adams

Black users have long been one of Twitter’s most engaged demographics, flocking to the platform to steer online culture and drive real-world social change. But a month after Elon Musk took over, some Black influencers are eyeing the exits just as he races to shore up the company’s business.

Several high-profile Black users announced they were leaving Twitter in recent weeks, as researchers tracked an uptick in hate speech, including use of the N-word, after Musk’s high-profile Oct. 27 takeover. The multibillionaire tech executive has tweeted that activity is up and hate speech down on the platform, which he said he hopes to make a destination for more users.

At the same time, he posted a video last week showing company T-shirts with the #StayWoke hashtag created by Twitter’s Black employee resource group following the deaths of Black men that catalyzed the Black Lives Matter movement, including the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown. His post contained laughing emojis, and someone can be heard snickering off-camera as the T-shirts are displayed.

Musk later posted and then deleted a tweet about the protests — fueled in part by activists on Twitter — that followed in Ferguson, Missouri, pointing to a subsequent Justice Department report and claiming the slogan “‘Hands up don’t shoot’ was made up. The whole thing was a fiction.”

He has also moved to restore many banned accounts despite condemnation from civil rights groups such as the NAACP, which accused him of allowing prominent users “to spew hate speech and violent conspiracies.” Civil rights leaders have also urged advertisers to withdraw over concerns about his approach to content moderation.

Twitter didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In a blog post it published Wednesday, the company said its “approach to experimentation” has changed but not any of its policies, though “enforcement will rely more heavily on de-amplification of violative content: freedom of speech, but not freedom of reach…We remain committed to providing a safe, inclusive, entertaining, and informative experience for everyone.”

Downloads of Twitter and activity on the platform have risen since Musk took control, according to two independent research firms. The data lends support to his claims that he is growing the service, though some social media experts say the findings may not shed much light on the company’s longer-term prospects. And while there is no hard data on how many Black users have either joined or left the platform over that period, some prominent influencers say they’re actively pursuing alternatives.

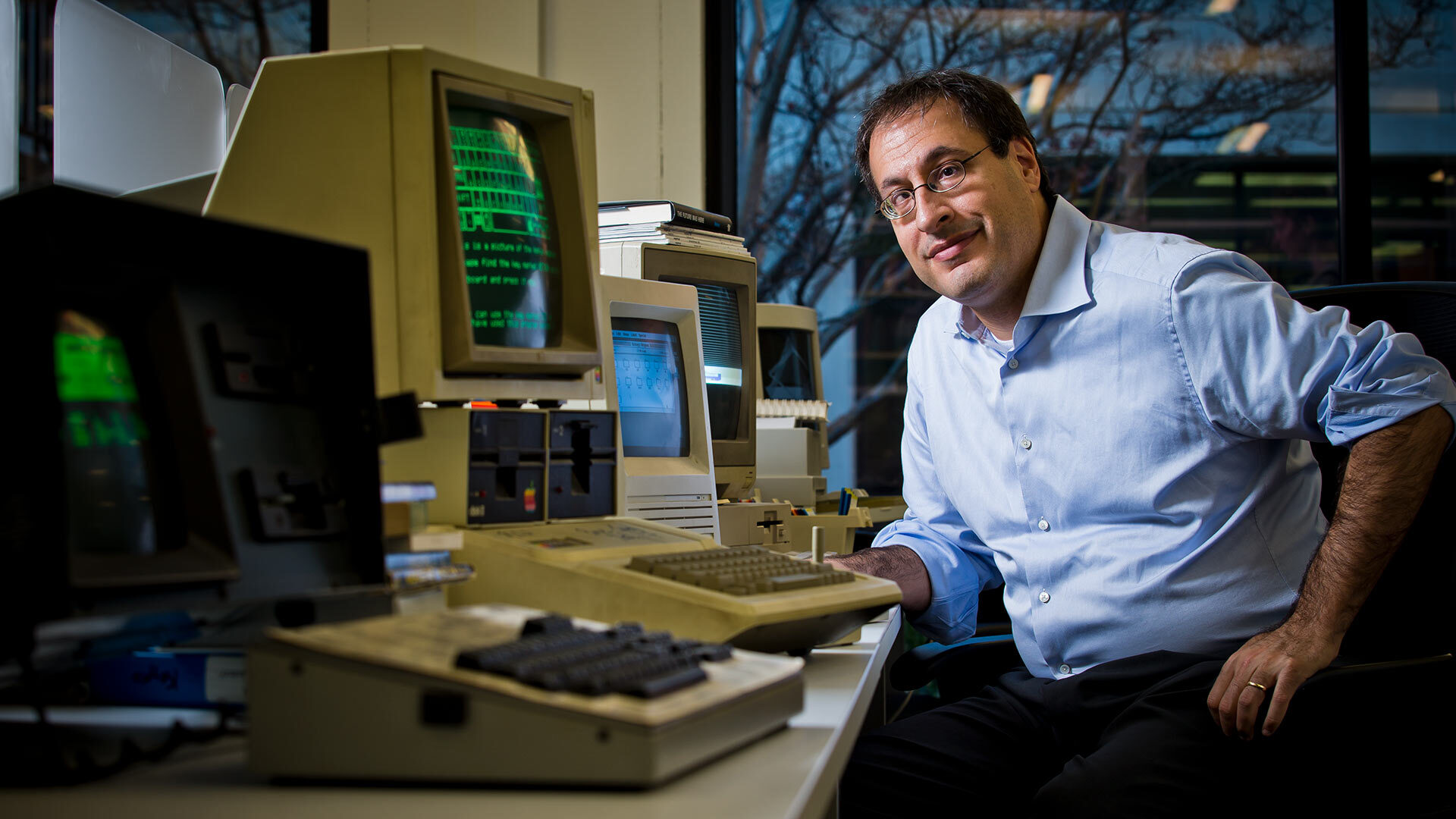

Jelani Cobb, a writer for The New Yorker and the dean of the Columbia Journalism School, said he has joined two decentralized microblogging apps — Mastodon and Post News — after leaving Twitter, telling his nearly 400,000 followers last week that he’d “seen enough.” The reinstatement of former President Donald Trump’s account was the “last straw,” he told NBC News.

Jelani Cobb at an event in New York.Roy Rochlin / Getty Images for Unfinished Live

Jelani Cobb at an event in New York.Roy Rochlin / Getty Images for Unfinished Live

“I can say confidently that I will not return to Twitter as long as Elon owns it,” he said. “Some people think that by staying on the site they’re being defiant, defying the trolls, the incels, the ill-will they’re encountering. But Elon Musk benefits from every single interaction people have on that platform. That was the reason I left. There are some battles you can only win by not fighting.”

Imani Gandy, a journalist and the co-host of the podcast “Boom! Lawyered” (@AngryBlackLady, 270,000 followers), recently tweeted that she isn’t enthused enough by Twitter alternatives to switch platforms.

The longtime Twitter user said in an interview that a combination of blocking, filters and “community-based accountability when it comes to anti-Blackness” make her less inclined to leave, for now. “Sure there are Nazis and jerks on Twitter, but they’re the same Nazis and jerks that have always been there, and I’m used to them,” she said.

Fanbase, another social media app, has seen usership jump 40% within the last two weeks, according to its founder, Isaac Hayes III. “We contribute so much to the culture and the actual economy of these platforms,” he said, “but do we own them?”

Investors in the service, which lets users monetize their followings by offering subscriptions, include Black celebrities such as the rapper Snoop Dogg and the singer and reality TV star Kandi Burruss. Other Fanbase investors — including the often polarizing media personality Charlamagne Tha God (2.15 million Twitter followers) and former CNN analyst Roland Martin (675,000 followers) — have touted it as a Twitter alternative.

For more than a decade, the community known as “Black Twitter” — an unofficial group of users self-organized around shared cultural experiences that convenes sometimes viral discussions of everything from social issues to pop culture — has played a key role in movements such as #SayHerName and #OscarsSoWhite.

In 2018, Black Americans accounted for an estimated 28% of Twitter users, roughly double the proportion of the U.S. Black population, according to media measurement company Nielsen. As of this spring, Black Americans were 5% more likely than the general population to have used Twitter in the last 30 days — second only to Asian American users, it said.

Some signs indicate a slowdown among Black Twitter users that predates Musk. In April, the rate of growth among Black Twitter users was already slower than any other ethnic group on the platform: 0.8% in 2021, down from 2.5% the previous year, according to estimates provided by Insider Intelligence eMarketer. (Growth among white users was 3.6%, down from 6%.)

A recent Reuters report cited internal Twitter research pondering a post-pandemic “absolute decline” of heavy tweeters — which the report described as comprising less than 10% of monthly users but 90% of global tweets and revenue. Twitter told Reuters that its “overall audience has continued to grow.”

Catherine Knight Steele, a communications professor at the University of Maryland and the author of “Digital Black Feminism,” said the departures of Black celebrities may not foreshadow a broader exodus, but she expects Black Twitter users to engage less on the platform over time.

If that bears out, she said, “without a robust Black community on Twitter, the only path forward for the site is to increasingly lose relevance as it becomes more inundated with more hatred and vitriol,” risking further panic among advertisers. The watchdog group Media Matters estimated last week that nearly half of Twitter’s top 100 advertisers had either announced or appeared to suspend their campaigns within Musk’s first month at the helm.

Any decline among highly engaged user segments would add pressure on Twitter’s business, analysts say, as 90% of the company’s revenue last year came from advertising.

“No platform wants to alienate any group of users, particularly an incredibly active group of users,” said Jasmine Enberg, principal analyst at Insider Intelligence eMarketer. “Twitter’s value proposition to advertisers has long been the quality and the engagement of its core user base … so the more that that addressable audience becomes diluted, both in terms of size and in terms of engagement, the less attractive the platform becomes.”

Steele said she has seen Black women in particular disengage amid threats and harassment over the last few years. And in recent weeks, high-profile Black women have been among the most vocal about leaving the platform.

TV powerhouse Shonda Rhimes tweeted to her 1.9 million followers in late October that she’s “Not hanging around for whatever Elon has planned. Bye.” Rhimes, who didn’t respond to a request for comment, has had an outsize stature on the app — having helped popularize live-tweeting with her Thursday night “Shondaland” block on ABC. The practice has been offered a proof point for advertisers wary of marrying Twitter and TV.

Other celebrities including the singer Toni Braxton (1.8 million Twitter followers) and Whoopi Goldberg (1.6 million followers) have also announced their departures, citing concerns about hate speech. The Oscar- and Emmy-winning co-host of “The View” said on the ABC talk show that she is “done with Twitter” for now. “I’m going to get out, and if it settles down and I feel more comfortable, maybe I’ll come back,” she said. Representatives for Braxton and Goldberg didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Steele said the history of Black communities’ withdrawal from other arenas, including offline, bodes ill for Twitter if it can’t turn the tide.

“It’s crippling to the economies of cities when Black folks leave, platforms when Black folks leave, entertainment sites when Black folks leave,” she said. “Twitter would suffer a similar fate.”

Steele said she has seen Black women in particular disengage amid threats and harassment over the last few years. And in recent weeks, high-profile Black women have been among the most vocal about leaving the platform.

TV powerhouse Shonda Rhimes tweeted to her 1.9 million followers in late October that she’s “Not hanging around for whatever Elon has planned. Bye.” Rhimes, who didn’t respond to a request for comment, has had an outsize stature on the app — having helped popularize live-tweeting with her Thursday night “Shondaland” block on ABC. The practice has been offered a proof point for advertisers wary of marrying Twitter and TV.

Other celebrities including the singer Toni Braxton (1.8 million Twitter followers) and Whoopi Goldberg (1.6 million followers) have also announced their departures, citing concerns about hate speech. The Oscar- and Emmy-winning co-host of “The View” said on the ABC talk show that she is “done with Twitter” for now. “I’m going to get out, and if it settles down and I feel more comfortable, maybe I’ll come back,” she said. Representatives for Braxton and Goldberg didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Steele said the history of Black communities’ withdrawal from other arenas, including offline, bodes ill for Twitter if it can’t turn the tide.

“It’s crippling to the economies of cities when Black folks leave, platforms when Black folks leave, entertainment sites when Black folks leave,” she said. “Twitter would suffer a similar fate.”

Jelani Cobb at an event in New York.Roy Rochlin / Getty Images for Unfinished Live

Jelani Cobb at an event in New York.Roy Rochlin / Getty Images for Unfinished Live